Damned if You Do, Damned if You Don’t

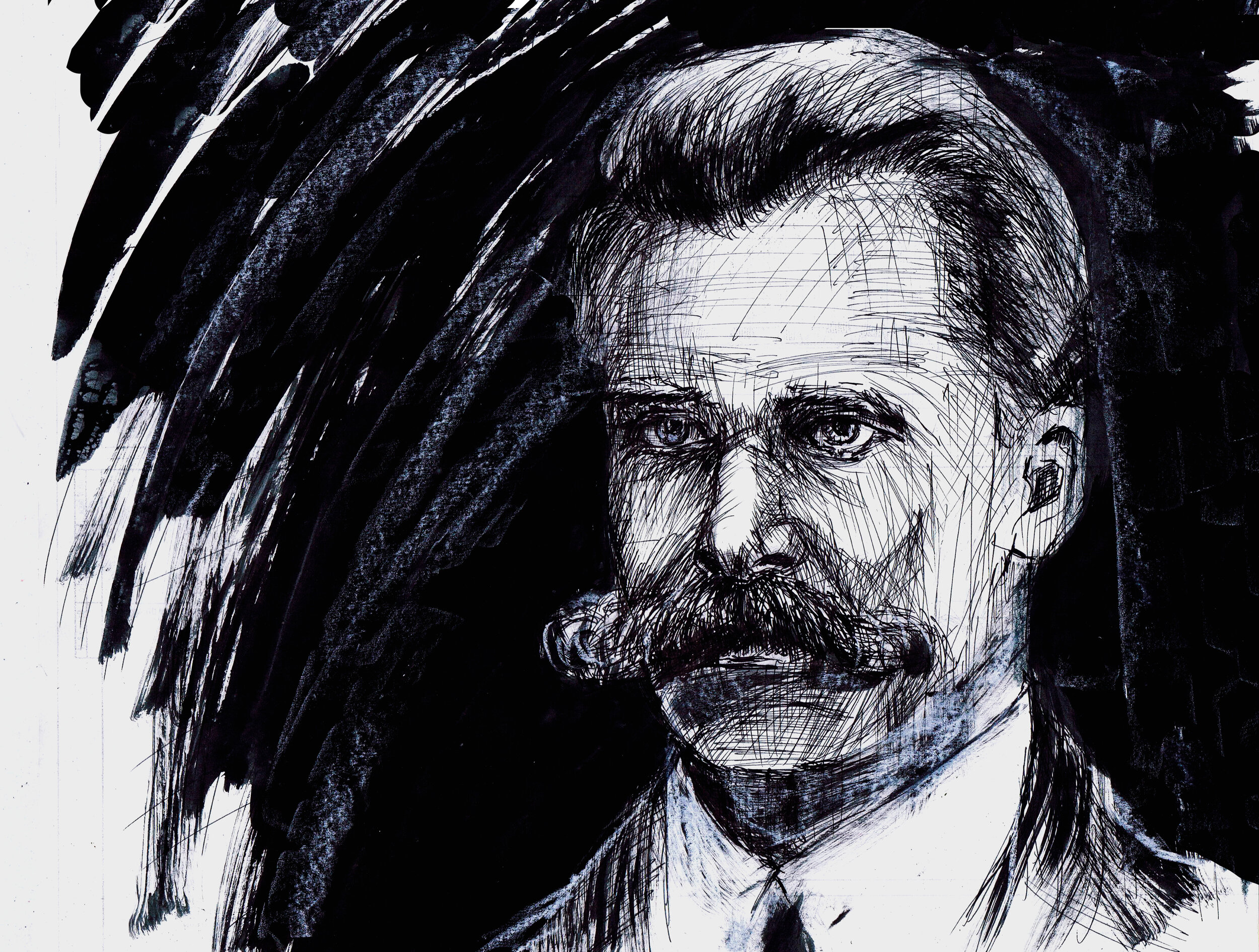

By/Par German Vizulis (Shutterstock.com)

Mishel Alexandrovsky

(FR) Dans la Généalogie de la morale, Nietzsche aborde l’évolution de notre conception moderne du « mal » : comment la perception de la morale a été révisée de force à pureté, où mauvaise conscience est devenue morale, où la culpabilité naquit, et la souffrance devenue significative. L’analyse du « mal » par Nietzsche se concentre sur son scepticisme à l’égard de l’existence élémentaire du mal, la soif de pouvoir du peuple, et le préjudice potentiel résultant de ce concept du « mal ». Cette considération propose une approche nihiliste sur la perception de la morale, tout en assumant le pire chacun. La distinction fictive entre bon et mauvais, où cet artifice peut être un guide utile pour notre opération dans ce monde. Même si beaucoup sont, en effet, avides de pouvoir et dominateurs, le bon est toujours possible et préférable pour certains, et s’efforcer d’agir de la sorte peut être un objectif noble et une bonne manière de contrebalancer un relativisme suicidaire.

In The Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche discusses the evolution of our modern concept of “evil.” Nietzche considers how: the focus of morality shifted from strength to purity, bad conscience became moralized, guilt came into existence, and suffering was made meaningful. Nietzsche’s analysis of “evil” centres around his scepticism of its very existence, the craving people have for power, and the potential harm that results from the creation of a concept like “evil.” This account provides a nihilistic perspective of morality, while also assuming the worst of people. The invented distinction between good and evil, while artificial, still serves as a guide for our operation in the world. Even if many are, indeed, power-hungry and domineering, good is still possible and preferable; striving toward goodness is a righteous purpose that counterbalances suicidal nihilism.

1. As It Began, So Shall It End

Nietzsche starts with a naturalistic explanation of the origins of “evil” and morality themselves. The good versus bad ideals originated in the noble warrior class, where strength constituted goodness, and weakness constituted evil. These ideals evolved into the ideals of the priestly class wherein goodness was synonymous with purity, and evil with impurity. The latter was thought to be achieved by viewing cleverness, as opposed to physical ability, as a strength, thus providing the traditionally weak masses with a sense of power that they craved. In turn, the responsibility of overriding the instinct for dominance was placed on those traditionally understood as strong. The priestly class defined what was “good” according to the negation of their concept of “evil,” which referred to bringing about responsibility and guilt. As a result, the priestly class deemed the ways of the noble class immoral, allowing the priestly class to gain power over the nobles, thus creating new and potentially harmful values. Consequently, Nietzche questions the existence of a moral system as anything other than an instrument of power.

According to Nietzsche, it is not enough to reduce the origins of morality to evolutionary processes by which acts that serve others are deemed “good.” Nietzsche deems the presumption that morality arose as a means to build society implausible; he claims that the praise of certain qualities is selfish and self-serving, and that any focus on judging others instead of improving oneself is not what morality ought to be. Nietzsche argues, therefore, that the concept of "evil" was entirely invented.

2. Suffering is Key

Our moral compass was, in Nietzsche’s view, acquired through the development of memory. Specifically, our ability to recall debts allows us to feel guilty (or, rather, indebted). The punishment of a failed debtor was used as an expression of the creditor’s anger prior to the moralization of debt, demonstrating the human instinct for cruelty and dominance; Nietzsche notes that the origin of punishment is the desire to overpower the wrongdoer and exact revenge. However, the constraints of society forbid us from expressing our instinct for dominance, causing us to turn such instincts inwards and create a bad conscience through which we torture ourselves.

In opposition to the priestly ascetic ideals of self-denial and self-restraint, we use perceived debt to our ancestors for their sacrifice and piety to God due to our believed sins and transgressions, as means of creating guilt and a need for self-punishment. This seeking out of suffering is just another way of attempting to gain control over oneself in a world where we have so little control otherwise. Facilitating our own suffering allows us to have a comprehensible enemy, as well as a feasible method to overcome it. We foster this guilt, which is representative of evil, in ourselves since we would rather suffer than exist without meaning.

3. To Make Meaning

We have no way of knowing whether free will is real or whether we are driven by our instincts for power. However, if we assume that we do not have a choice, we will be unable to function without falling into hopelessness. Nietzsche points out that the invention of ascetic ideals creates meaning outside of real life; the denial of our natural instincts allows us the sense of control that we all seek. Our well-being is based on feeling as though we have purpose, more than it is based on positive experiences; we can survive suffering when we ascribe meaning to it. Leading a hedonistic life does not allow for a true sense of fulfilment, as the creation of a purpose saves us from getting lost in our endless philosophical musings.

Since we exist as conscious beings with an understanding of the notion of morality—of one action being better than the other—we are responsible for our own improvement. Regardless of the meaninglessness of morality, striving to improve ourselves allows us to create our own subjective meanings. Thus, to avoid the suicidal nihilism that Nietzsche tries to resolve, we must acknowledge the existence of at least some meaning. Additionally, if we are to operate under uncertainty, not knowing the rules we are expected to follow, nor the consequences of disobedience, we can still engage in philosophical discussion to understand the best way to operate. It is impossible to know anything with full certainty, so it is therefore impossible to assume that all humans are cruel. The reduction of human will to just one facet belittles its complexity. Thus, if human goodness is a possibility, we must strive for it, and have the desire for improvement be our subjective meaning.